When the Norwegian author of the Minnesota Trilogy was in the U.S. as the third book was released, I was lucky enough to ask him some questions at my favorite bookstore, Once Upon a Crime, as I once did with Jussi Adler-Olsen. Here are my notes from that conversation.

Can you tell us about yourself and your writing career? How did you come to write the Minnesota Trilogy?

The Minnesota Trilogy started because I met a woman and I liked her and she, for some reason, liked me and she turned out to be American, so I moved to the States. I found myself living in Kentucky. My wife was applying for jobs all across the country. She is a biologist . She applied for jobs with the forest service and got a job offer in the northeast corner of Minnesota on the north shore, Superior National Forest, at the Tofte ranger station. So I ended up among the Norwegian

Tofte ranger station built in the 1930s, now used for seasonal housing. Photo courtesy of the National Forest Service.

Americans. When I came up there, it was very tempting for me as a Norwegian writer. I came across something that was both very familiar and very exotic. There were several things I recognized very well from Norway, not just names but the way of thinking, the way of speaking – or not speaking. It was on the other side of the globe, and there were the Ojibwe people and the history of the French fur traders. There were a lot of things going on, so I felt very early on that I wanted to write something substantial.

For several years I had been wanting to write a crime novel that would include more than just a plot – who killed Mr. X. I wanted to write a crime story that includes the whole community and the history of the community and the landscape, and nature, the bonds between the people and the landscape. Living on the North Shore I realized I had the perfect setting.

On the fourth of July, 2004, my wife and I drove up to Canada. We drove along the shore on highway 61 going to Thunder Bay to buy . . . I don’t know what. Prescription drugs. Canadian bacon. On the way we passed this little motel called The Whispering Pines and my wife said “doesn’t that look like the murder scene from a mystery?” Death at Whispering Pines. We started musing just for fun about who might have gotten

photo of Lake Superior courtesy of fritzmb

killed there. Perhaps a Norwegian tourist who had come to visit his distant cousins and had been killed in some eccentric Norwegian-American way – poisoned by lutefisk or something, And then we started to imagine what kind of policeman might start to investigate the murder on the North Shore. We based these musings on our own experience with a male of the North Shore, so to speak, and we went on doing this every time we went on a road trip, which we did quite often because my wife had never lived in Minnesota. We explored the state and every time we ran out of something to talk about we picked up the thread and began talking about this policeman again and asked each other questions. Would he be married? Divorced? Does he have children? What does he like, does he hate, what kind of food does he eat, does he drink, does he smoke? And not least, what would his name be? That sounds like a simple thing, but it took a long time. A colleague of my wife’s had a cute little boy, four or five years old. When heard his name was Lance I thought: that’s his name – Lance Hansen.

After a year or so of talking about this shadowy character we had built a whole world around him, his relatives, his background story, his family’s immigration from Norway. I could pretty much start writing when I came back to Norway. My wife did most of the work, though I did write the books. That was my first crime story.

photo of the author courtesy of Shea Sundstøl

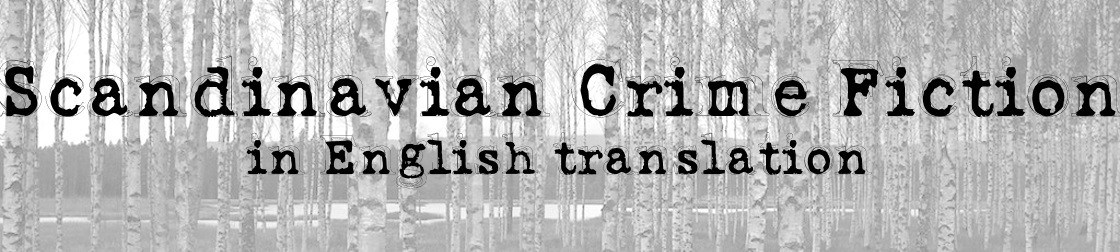

All three books follow “forest cop” Lance Hansen’s determination to solve two crimes – first, the murder of a Norwegian tourist, bludgeoned to death while camping on the shore of Lake Superior, and the other the possible murder of Swamper Caribou in the late 19th century. Most mysteries are self-contained. Readers have a sense of resolution by the end of a book, but this is really a trilogy. Why did you decide to tell these stories in a trilogy rather than as a single big fat mystery?

I could have written it as one big fat mystery, but then I really wanted . . . the middle book is very different. It’s very short, it’s intense, and it takes place over one or two days, and I really wanted to do that, I think the crime genre needs more than any other genre to be challenged on the narrative structure. Obviously there are some ground rules you have to follow when you write about crime, but within that framework you can do quite a lot, things that people haven’t come up with before. So it was partly that I wanted to do something a little bit different but mostly because when I started thinking about this story up on the North Shore it crystallized that way, with a very intense hunting scene in the middle of everything. I could have sold more books and made more money if I had written a more traditional trilogy. I think a lot of people thought when they opened the second book, “what on earth is this?”

Can you tell us about the titles of the three books – how did you decided on them; what do they mean?

The Land of Dreams – it was the land of dreams to immigrants, and it was the land of dreams in the sense that it was once inhabited by the Ojibwe whose culture is very much focused on the interpretation of dreams. And also when I started thinking about this, I thought I would create a very masculine policeman in a blue collar, rural environment, but I wanted to give him some kind of handicap, one that he couldn’t speak about to others. It struck me that if he couldn’t dream, he couldn’t complain to his colleagues about it. They would ridicule him. So he longs to dream again. Only the Dead (In Norwegian “the dead” in plural) I wanted to send this man through the valley of death. The middle book is the lowest point of this valley of death. It’s also the ice-cold heart of the whole trilogy. The third book, The Ravens – I couldn’t come up with a title. We had a competition at the publisher’s and people were writing long lists of titles. At the end I just had to call it something. There are quite a few ravens in the book, and it sounds gothic.

Both murders have intimate family connections for Lance. There are some real tensions in this family – particularly between Lance and Andy – but also a kind of fierce connection and protectiveness. Can you talk a bit about these relationships and how they shape the story?

It’s kind of a Cain and Abel story. I have two brothers and I have good relationships with both of them. I don’t go hunting with them, though.

You have to remember that I’m Norwegian, so I know a lot about the law of silence, there are certain things you don’t speak about, which also goes for a lot of Norwegian Americans. That’s the bad side of the heritage. The reason I felt capable of portraying people on the North Shore – I only lived there for two years and I didn’t really speak to too many people because, well, they don’t speak much. So I sat indoors writing other books, but I had this feeling that I knew who they were intuitively, that these were my people. I know the types, I know why they don’t speak, what they aren’t saying. I could just has well have written the book about Norway, where I come from. My family has never been as burdened as this family, but here is the same dynamic of covering up things, not talking about things and then finally, one day, everything unravels because of it. That combined with a strong sense of family loyalty can make the knot very hard, very tight.

At one point in The Ravens, Lance thinks, “Deciding not say anything was always the preferred solution to every problem.” Lance has become almost a Hamlet figure. He’s obsessed and feels compelled to confront his brother with his suspicions, but he faces paralyzing dread. He’s afraid of his brother, but seems more afraid of the shame that his family will experience. What’s going on with Lance?

The thing is that it’s through this introspection that he manages to solve the case. That was something I wanted to do, write a murder mystery and portray a man in his full inner life. His life is like a shipwreck when it starts. By the end he has a chance to start anew.

The violence in these books, while not gruesome by standards of the genre, is quite shocking in part because it seems to come out of some primitive part of people who feel a strange sense of release as they bludgeon someone to bits. Can you talk a bit about writing those scenes and what you think about graphic violence in crime fiction?

When I decided to write this murder mystery I wanted to have just one murder (though there is also one in the past). That’s one too many. It’s a tragedy, and I wanted to keep the focus on what a complete tragedy it is, not just for the one who dies but for everybody who was in the magnetic field around that murder and get their lives turned upside down. I’m not going to turn it into entertainment at all. The violence in these books is just in a couple of places, but I describe the violence in the same way that I would try to describe like a . . . like a love scene (which is very difficult to write, a physical love scene. If you want to make a fool of yourself, just write a sex scene).

If you want to do it, you have to do it right and in such a way that it actually imitates real violence, that a little bit of the original real life intensity is captured instead of just painting and painting and turning it into pornography. I wanted to do the same thing with these very few scenes of violence, that it’s really what it looks like and how it feels. Something that is very typical for violence – it’s over very soon, but afterwards is so completely shocking. You have to write it in such a way that the reader doesn’t get all caught up in the graphic descriptions of blood and gore but afterwards thinks, “ugh, what is this? It feels really unpleasant.” Because it does feel unpleasant.

There’s also a sense of sympathy for that experience in that Lance hits a cat with his car and has to kill the badly injured animal, and by putting him in that position it almost humanizes that experience.

Yes, and it also says something about how stressed he is and what kind of pressure he is under. My wife didn’t like it. My wife is very fond of cats.

The setting of these books is a huge factor – both the language you use to describe the North Shore and the lake, but also the mood and the presence of the lake in the story. What drew you to the setting and how does the lake in particular figure in the trilogy?

I remember when we first went to Minnesota, driving up from Lexington Kentucky. There’s a certain point when you come over the hill to Duluth and you see the whole expanse of the lake. It was such a surprise. I guess I’m sensitive to landscape, really tuned into that frequency, so it really stuck with me. In a way it started there – not the idea of a murder mystery, but that as I writer I wanted to write something huge and substantial about it. The whole structure, the form of this trilogy – so long, so slow – I wanted the whole thing to reflect the lake, this Minnesota landscape. You can’t have a lot of guys shooting with machine guns – well, you could, but it doesn’t suit the landscape. It’s like putting on a completely wrong dress or suit. The lake plays a significant role both on the surface of the text but also when you come to the structure of the trilogy.

And the interior life of Lance, because the lake plays such a role in his imagination and his confronting the unknown or what’s missing inside of him.

It becomes sort of – I never thought of it as symbol of anything, but I was very well aware of it as something you could put anything into (literally!).

One of the family secrets that Lance uncovers is that he has some Ojibwa ancestry. That family history that he cares so much about turns out to be full of holes and mistakes. The intersection of indigenous culture and European immigrants comes up again and again. What drew you to this combination of cultures?

When I decided to write something from the North Shore, I knew that it would include the Norwegian-Swedish immigration and the local history. Then I started to read the history of the area and didn’t have to read many pages before realizing the Ojibwe people have been there all the time and are still here and it would feel wrong for the project if I took a big piece of reality and brushed it under the carpet in the Norwegian way.

Ojibwe family circa 1900, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

I started to read a lot of Ojibwe mythology and folk tales, and I since I didn’t know any Ojibwes I wondered how to open a gateway. I came up with the character of Willie Dupree, an elder who had been a postman. I modeled him after my maternal grandfather. I grew up in the countryside of Telemark (a southern Norwegian county) and my mother’s family had always been closely connected to the forest. My maternal grandfather owned some forest land and had worked in the woods. I spent evenings with him listening to stories from his days as a logger and a hunter. Sometimes he would tell a story he’d told ten times before. He had the same relationship to the forest as a fisherman has to the ocean. I realized that might also be true for an old Ojibwe. So I based him on my grandfather and gave him a different set of stories. I sure my grandfather would have loved being portrayed this way.

Did you start writing the first book while you lived in the states?

No, in Norway. I was aware that I needed a certain distance to it. Sometimes as a writer reality gets in the way of the writing, so I knew the right time would be as soon as I was back in Norway when everything was fresh in my memory but I had the Atlantic ocean between me and the actual place. That way it became about my memories more than about the actual North Shore. I think that was perhaps one of the ways the whole trilogy got a sort of dreamy air to it. The North Shore was a place I really liked, and I missed it for several years, so it’s also a labor of love, a way to process the fact that I really missed it.

I had recently been on the North Shore before reading Land of Dreams and enjoyed encountering recognizable places and people. That’s fun for people here.

That makes me very happy. That’s probably the biggest compliment I’ve ever received as a writer is to meet people who say you got all these things – not just the geography. I met when I spoke at the American Swedish Institute I met a man who lived on the North Shore. Actually, his brother worked with my wife; it’s a little world. He said “you are the first one who has captured in words the eccentricity of the North Shore communities.” It was an enormous compliment to me and I thought that was probably the word for the trilogy – eccentric.

You had a terrific translator for this series, Tiina Nunnelly. Can you tell us a bit about the process of working with a translator? Were the books translated before the University of Minnesota press got involved?

The press got a sample translation, probably done by Tiina. When she had translated the first book I got an email from my editor at the press and he asked if I wanted to read through the whole manuscript. I’m a lazy person, so I try to find strategies to not have to work too much. I knew there was one page in the manuscript, where Lance has gone down to the lake the night after the murder. He stands there he looks at the lake, and there’s a description of the moonlight on the water and the rippling surface and how the moonlight is being broken up into many little pieces, and I knew that if she could translated that both to maintain the content but also the musicality and the flow of it . . . I think it was better, actually, than the original Norwegian!

How have Norwegian readers responded to the trilogy and has it differed from the ways Americans have responded?

It was very well received in Norway –

The Land of Dreams received the Riverton Prize, the most prestigious crime fiction prize in Norway.

So people liked them a lot but the big difference for Norwegians is that the environment is exotic. Everybody knows about Norwegian Americans. A majority of Norwegians have distant relatives here and a lot have kids who are studying here. There are a lot of bonds between the two peoples, but they found it pretty eccentric and exotic. But they really loved it. Here people feel that I am writing more about them, that’s the big difference. I must say I really enjoy talking to readers here. It’s something like I’m bringing this story about Lance home. On so many levels it means so much to me, both professionally but even more so personally, really. The only sad thing is that this is the last book, so probably the last chance I have to come here and talk to people.

What are you working on now?

I published a thriller in 2013, an archaeology thriller that takes place in Italy and Egypt, and now I’ve just finished a novel that will be out in August or September. It’s the first in a series. This time there will be a closed case in each one, but it won’t be set on the North Shore because I can’t afford to got here every time I want to check out something. So it’s set in Telemark, my home in Norway, which has a certain standing in Norwegian cultural history. It’s the heartland of everything that’s core Norwegian: the majority of Norwegian folklore and folk music and superstitions, such as the belief in little people. I’m taking that mythological dimension of Telemark, which is the mythological foundation of Norway, and making it the foundation of a mystery-crime universe.

That sounds . . . eccentric.

It is eccentric. It’s a bit like the Minnesota Trilogy in that it’s focused on the bonds between the landscape, the people who inhabit it, and the history of the landscape. In a way you can say the role that is played in the trilogy by the ghost of Swamper Caribou, the Ojibwe culture and dream interpretations, is played now by old Norwegian folk beliefs and superstitions.

Thanks to the author for letting me record this conversation and indulging my questions, to Once Upon a Crime for hosting the event (and by the way, you can support independent bookstores by buying all the mysteries you want there – they will happily mail books to you, hint, hint), and to the University of Minnesota Press and Tiina Nunnelly for bringing this award-winning work to American readers.

I have previously reviewed The Land of Dreams, Only the Dead, and The Ravens. You may also be interested in a post by the author about the special landscape of the North Shore at his publisher’s blog.

Because he saw his brother’s truck close to the scene of the crime, and because he knows Andy is probably gay (as were the Norwegian tourists) but ashamed of his sexual identity and has a history of committing extreme violence, Lance becomes convinced his brother may be a killer. In the second book of the trilogy, that suspicion makes a hunting expedition take a threatening turn as Lance and Andy stalk one another. Layered in this narrative is the story of their ancestor, a young Norwegian immigrant who has crossed the frozen lake and who is terrified by the Indian medicine man who is trying to help him. It’s an intense and disorienting book that leaves us hanging.

Because he saw his brother’s truck close to the scene of the crime, and because he knows Andy is probably gay (as were the Norwegian tourists) but ashamed of his sexual identity and has a history of committing extreme violence, Lance becomes convinced his brother may be a killer. In the second book of the trilogy, that suspicion makes a hunting expedition take a threatening turn as Lance and Andy stalk one another. Layered in this narrative is the story of their ancestor, a young Norwegian immigrant who has crossed the frozen lake and who is terrified by the Indian medicine man who is trying to help him. It’s an intense and disorienting book that leaves us hanging.

At Petrona Remembered,

At Petrona Remembered, dead. She says it has a well-constructed plot with a good ending though some of the characters in the fraying community can be hard to keep straight. She’s looking forward to the sequel, coming out in the UK soon.

dead. She says it has a well-constructed plot with a good ending though some of the characters in the fraying community can be hard to keep straight. She’s looking forward to the sequel, coming out in the UK soon.

e past, since he keeps seeing a man who appears to be from another time. And he’s haunted, too, by his suspicion that his brother Andy may be the man who killed the Norwegian visitor. That seems impossible when the detectives make an arrest, until Hansen uncovers another family secret: DNA evidence that the murderer had Indian ancestry had ruled Andy out as a suspect. But Hansen discovers that he and Andy have Ojibwe ancestry.

e past, since he keeps seeing a man who appears to be from another time. And he’s haunted, too, by his suspicion that his brother Andy may be the man who killed the Norwegian visitor. That seems impossible when the detectives make an arrest, until Hansen uncovers another family secret: DNA evidence that the murderer had Indian ancestry had ruled Andy out as a suspect. But Hansen discovers that he and Andy have Ojibwe ancestry. y the world he’s in and its savage inhabitants, determined to get his own piece of the new world. His story is interwoven with the hunt, each narrative growing more intense, more disturbing, less connected to what we think of as reality with each turning page. The natural world itself is transformed as an ices storm descends on the North Shore, making the woods beside the vast frozen lake a labyrinthine and disorienting forest of ice. It’s in this weird, frozen world where the past and present touch, where the hunter becomes the hunted, where things are stripped down to their elemental essence.

y the world he’s in and its savage inhabitants, determined to get his own piece of the new world. His story is interwoven with the hunt, each narrative growing more intense, more disturbing, less connected to what we think of as reality with each turning page. The natural world itself is transformed as an ices storm descends on the North Shore, making the woods beside the vast frozen lake a labyrinthine and disorienting forest of ice. It’s in this weird, frozen world where the past and present touch, where the hunter becomes the hunted, where things are stripped down to their elemental essence. photo of Baraga’s Cross courtesy of

photo of Baraga’s Cross courtesy of